This article is a part of a series of posts where I will walk through every line of the Rails default Dockerfile and explain the best practices and optimizations.

Docker images can be optimized in different ways that include, but are not limited to, image size reduction, build performance optimization, security, and maintainability best practices, and application-specific optimizations. In the first article, I will touch only image size reduction optimization and explain why they are important.

Why to optimize the image size?

As in every other process of software development, each developer will list his reasons why he wants to make his Docker builds faster. I will list the reasons that are most important to me.

Faster builds & deployments

Smaller images are faster to build because fewer files and layers need to be processed. This improves developer productivity, especially during iterative development cycles. Smaller images take less time to push to a registry and pull from it during deployments. This is especially critical in CI/CD pipelines where containers are built and deployed frequently.

Reduced storage costs & network bandwidth usage

Smaller images consume less storage on container registries, local development machines, and production servers. This reduces infrastructure costs, especially for large-scale deployments. Smaller images use less bandwidth when transferred between servers, especially important when you’re building images locally or in CI/CD pipelines and pushing them to a registry.

We spent $3.2m on cloud in 2022... We stand to save about $7m in server expenses over five years from our cloud exit.

Improved performance & security

Smaller images require fewer resources (e.g., CPU, RAM) to load and run, improving the overall performance of containerized applications. Faster startup times mean your services are ready more quickly, which is crucial for scaling and high-availability systems. Minimal base images like alpine or debian-slim contain fewer pre-installed packages, decreasing the risk of unpatched or unnecessary software being exploited.

Besides everything mentioned above, removing unnecessary files and tools minimizes distractions when diagnosing issues and leads to better maintainability and reduced technical debt.

Inspecting Docker images

To get different parameters of the image, including the the size, you can either look at the Docker Desktop or run the docker images command in the terminal.

➜ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

kamal-dashboard latest 673737b771cd 2 days ago 619MB

kamal-proxy latest 5f6cd8983746 6 weeks ago 115MB

docs-server latest a810244e3d88 6 weeks ago 1.18GB

busybox latest 63cd0d5fb10d 3 months ago 4.04MB

postgres latest 6c9aa6ecd71d 3 months ago 456MB

postgres 16.4 ced3ad69d60c 3 months ago 453MB

Knowing the size of the image does not give you the full picture. You don’t know what is inside the image, how many layers it has, or how big each layer is. A Docker image layer is a read-only, immutable file system layer that is a component of a Docker image. Each layer represents a set of changes made to the image’s file system, such as adding files, modifying configurations, or installing software.

Docker images are built incrementally, layer by layer, and each layer corresponds to an instruction in the Dockerfile. To get the layers of the image, you can run the docker history command.

➜ docker history kamal-dashboard:latest

IMAGE CREATED CREATED BY SIZE COMMENT

673737b771cd 4 days ago CMD ["./bin/thrust" "./bin/rails" "server"] 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago EXPOSE map[80/tcp:{}] 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago ENTRYPOINT ["/rails/bin/docker-entrypoint"] 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago USER 1000:1000 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago RUN /bin/sh -c groupadd --system --gid 1000 … 54MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago COPY /rails /rails # buildkit 56.2MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago COPY /usr/local/bundle /usr/local/bundle # b… 153MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago ENV RAILS_ENV=production BUNDLE_DEPLOYMENT=1… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago RUN /bin/sh -c apt-get update -qq && apt… 137MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 4 days ago WORKDIR /rails 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago CMD ["irb"] 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago RUN /bin/sh -c set -eux; mkdir "$GEM_HOME";… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV PATH=/usr/local/bundle/bin:/usr/local/sb… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV BUNDLE_SILENCE_ROOT_WARNING=1 BUNDLE_APP… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV GEM_HOME=/usr/local/bundle 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago RUN /bin/sh -c set -eux; savedAptMark="$(a… 78.1MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV RUBY_DOWNLOAD_SHA256=018d59ffb52be3c0a6d… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV RUBY_DOWNLOAD_URL=https://cache.ruby-lan… 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV RUBY_VERSION=3.4.1 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago ENV LANG=C.UTF-8 0B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago RUN /bin/sh -c set -eux; mkdir -p /usr/loca… 19B buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago RUN /bin/sh -c set -eux; apt-get update; a… 43.9MB buildkit.dockerfile.v0

<missing> 3 weeks ago # debian.sh --arch 'arm64' out/ 'bookworm' '… 97.2MB debuerreotype 0.15

Since I already provided theory about images, and layers, it is time to explore the Dockerfile. Starting from Rails 7.1, the Dockerfile is generated with the new Rails application. Below is an example of what it may look like.

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

# check=error=true

# Make sure RUBY_VERSION matches the Ruby version in .ruby-version

ARG RUBY_VERSION=3.4.1

FROM docker.io/library/ruby:$RUBY_VERSION-slim AS base

# Rails app lives here

WORKDIR /rails

# Install base packages

# Replace libpq-dev with sqlite3 if using SQLite, or libmysqlclient-dev if using MySQL

RUN apt-get update -qq && \

apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y curl libjemalloc2 libvips libpq-dev && \

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists /var/cache/apt/archives

# Set production environment

ENV RAILS_ENV="production" \

BUNDLE_DEPLOYMENT="1" \

BUNDLE_PATH="/usr/local/bundle" \

BUNDLE_WITHOUT="development"

# Throw-away build stage to reduce size of final image

FROM base AS build

# Install packages needed to build gems

RUN apt-get update -qq && \

apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y build-essential curl git pkg-config libyaml-dev && \

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists /var/cache/apt/archives

# Install application gems

COPY Gemfile Gemfile.lock ./

RUN bundle install && \

rm -rf ~/.bundle/ "${BUNDLE_PATH}"/ruby/*/cache "${BUNDLE_PATH}"/ruby/*/bundler/gems/*/.git && \

bundle exec bootsnap precompile --gemfile

# Copy application code

COPY . .

# Precompile bootsnap code for faster boot times

RUN bundle exec bootsnap precompile app/ lib/

# Precompiling assets for production without requiring secret RAILS_MASTER_KEY

RUN SECRET_KEY_BASE_DUMMY=1 ./bin/rails assets:precompile

# Final stage for app image

FROM base

# Copy built artifacts: gems, application

COPY --from=build "${BUNDLE_PATH}" "${BUNDLE_PATH}"

COPY --from=build /rails /rails

# Run and own only the runtime files as a non-root user for security

RUN groupadd --system --gid 1000 rails && \

useradd rails --uid 1000 --gid 1000 --create-home --shell /bin/bash && \

chown -R rails:rails db log storage tmp

USER 1000:1000

# Entrypoint prepares the database.

ENTRYPOINT ["/rails/bin/docker-entrypoint"]

# Start server via Thruster by default, this can be overwritten at runtime

EXPOSE 80

CMD ["./bin/thrust", "./bin/rails", "server"]

Below I will provide a list of approaches and rules that where applied to the Dockerfile above to make the final image size efficient.

Optimize packages installations

I am sure you keep only needed software on your local development machine. The same should be applied to Docker images. In the examples below I will consistently making worse the Dockerfile extracted from the Rails Dockerfile above. I will reference it as an original Dockerfile version.

Rule #1: Use minimal base images

FROM docker.io/library/ruby:$RUBY_VERSION-slim AS base

The base image is the starting point for the Dockerfile. It is the image that is used to create the container. The base image is the first layer in the Dockerfile, and it is the only layer that is not created by the Dockerfile itself.

The base image is specified with the FROM command, followed by the image name and tag. The tag is optional, and if not specified, the latest tag is used. The base image can be any image available on Docker Hub or any other registry.

In the Dockerfile about, we are using the ruby image with the 3.4.1-slim tag. The ruby image is the official Ruby image available on Docker Hub. The 3.4.1-slim tag is a slim version of the Ruby image that is based on the debian-slim image. While the debian-slim image is a minimal version of the Debian Linux image that is optimized for size. Look at the table below to get an idea of how smaller the slim image is.

➜ docker images --filter "reference=ruby"

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

ruby 3.4.1-slim 0bf957e453fd 5 days ago 219MB

ruby 3.4.1-alpine cf9b1b8d4a0c 5 days ago 99.1MB

ruby 3.4.1-bookworm 1e77081540c0 5 days ago 1.01GB

219 MB instead of 1GB — a huge difference. But what if the alpine image is even smaller? The alpine image is based on the Alpine Linux distribution, which is a super lightweight Linux distribution that is optimized for size and security. Alpine uses the musl library (instead of glibc) and busybox (a compact set of Unix utilities) instead of GNU counterparts. While it is technically possible to use the alpine image to run Rails, I will not cover it in this article.

Rule #2: Minimize layers

RUN apt-get update -qq && \

apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y curl libjemalloc2 libvips libpq-dev && \

rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists /var/cache/apt/archives

Each RUN, COPY and FROM instruction in Dockerfile creates a new layer. The more layers you have, the bigger the image size. This is why the best practice is to combine multiple commands into a single RUN instruction. To illustrate this point, let’s look at the example below.

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

# check=error=true

# Make sure RUBY_VERSION matches the Ruby version in .ruby-version

ARG RUBY_VERSION=3.4.1

FROM docker.io/library/ruby:$RUBY_VERSION-slim AS base

RUN apt-get update -qq

RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y curl

RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y libjemalloc2

RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y libvips

RUN apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y libpq-dev

RUN rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists /var/cache/apt/archives

CMD ["echo", "Whalecome!"]

I have split the RUN instruction into multiple lines, which obviously makes them more human-readable. But how will it affect the size of the image? Let’s build the image and check it out.

➜ time docker build -t no-minimize-layers --no-cache -f no-minimize-layers.dockerfile .

0.31s user 0.28s system 2% cpu 28.577 total

It took 28 seconds to build the image, while to build the original version with minimized layers takes only 19 seconds (almost 33% faster).

➜ time docker build -t original --no-cache -f original.dockerfile .

0.25s user 0.28s system 2% cpu 19.909 total

Let’s check the size of the images.

➜ docker images --filter "reference=*original*" --filter "reference=*no-minimize*"

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

original latest f1363df79c8a 8 seconds ago 356MB

no-minimize-layers latest ad3945c8a8ee 43 seconds ago 379MB

The image with minimized layers is 23 MB smaller than the one with no minimized layers. This is a 6% reduction in size. While it seems like a small difference in this example, the difference will be much bigger if you split all the RUN instructions into multiple lines.

Rule #3: Install only what needed

By default, apt-get install installs the recommended packages as well as packages you asked it to install. The --no-install-recommends option tells apt-get to install only the packages that are explicitly specified and not the recommended ones.

➜ time docker build -t without-no-install-recommends --no-cache -f without-no-install-recommends.dockerfile .

0.33s user 0.30s system 2% cpu 29.786 total

➜ docker images --filter "reference=*original*" --filter "reference=*recommends*"

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

without-no-install-recommends latest 41e6e37f1e2b 3 minutes ago 426MB

minimize-layers latest dff22c85d84c 17 minutes ago 356MB

As you can see, the image without --no-install-recommends is 70 MB bigger than the original one. This is a 16% increase in size.

dive utility to see which files were added to the image – read more about it in the end of the article.

Rule #4: Clean up after installations

The original Dockerfile includes the rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/* /var/cache/apt/archives command after the apt-get install command. This command removes the package lists and archives that are no longer needed after the installation. Let’s see how it affects the image size, to achieve that, I will create a new Dockerfile without the cleaning command.

RUN apt-get update -qq && \

apt-get install --no-install-recommends -y curl libjemalloc2 libvips libpq-dev

Building the images takes almost the same time as the original one, which makes sense.

➜ time docker build -t without-cleaning --no-cache -f without-cleaning.dockerfile .

0.28s user 0.30s system 2% cpu 21.658 total

Let’s check the size of the images.

➜ docker images --filter "reference=*original*" --filter "reference=*cleaning*"

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

without-cleaning latest 52884fe50773 2 minutes ago 375MB

original latest f1363df79c8a 16 minutes ago 356MB

The image without cleaning is 19 MB bigger than the one with cleaning, this is a 5% increase in size.

The worst scenario

What if all four optimizations mentioned above are not applied? Let’s create a new Dockerfile without any optimizations and build the image.

# syntax=docker/dockerfile:1

# check=error=true

ARG RUBY_VERSION=3.4.1

FROM docker.io/library/ruby:$RUBY_VERSION AS base

RUN apt-get update -qq

RUN apt-get install -y curl

RUN apt-get install -y libjemalloc2

RUN apt-get install -y libvips

RUN apt-get install -y libpq-dev

CMD ["echo", "Whalecome!"]

➜ time docker build -t without-optimizations --no-cache -f without-optimizations.dockerfile .

0.46s user 0.45s system 1% cpu 1:02.21 total

Wow, it took more than a minute to build the image.

➜ docker images --filter "reference=*original*" --filter "reference=*without-optimizations*"

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

without-optimizations latest 45671929c8e4 2 minutes ago 1.07GB

original latest f1363df79c8a 27 hours ago 356MB

The image without optimizations is 714 MB bigger than the original one, this is a 200% increase in size. This clearly shows how important it is to optimize the Dockerfile, larger images take more time to build and consume more disk space.

Always use .dockerignore

The .dockerignore file is similar to the .gitignore file used by Git. It is used to exclude files and directories from the context of the build. The context is the set of files and directories that are sent to the Docker daemon when building an image. The context is sent to the Docker daemon as a tarball, so it is important to keep it as small as possible.

If, for any reason, you don’t have the .dockerignore file in your project, you can create it manually. I suggest you use the official Rails .dockerignore file template as a starting point. Below is an example of what it may look like.

# See https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/builder/#dockerignore-file for more about ignoring files.

# Ignore git directory.

/.git/

/.gitignore

# Ignore bundler config.

/.bundle

# Ignore all environment files.

/.env*

# Ignore all default key files.

/config/master.key

/config/credentials/*.key

# Ignore all logfiles and tempfiles.

/log/*

/tmp/*

!/log/.keep

!/tmp/.keep

# Ignore pidfiles, but keep the directory.

/tmp/pids/*

!/tmp/pids/.keep

# Ignore storage (uploaded files in development and any SQLite databases).

/storage/*

!/storage/.keep

/tmp/storage/*

!/tmp/storage/.keep

# Ignore assets.

/node_modules/

/app/assets/builds/*

!/app/assets/builds/.keep

/public/assets

# Ignore CI service files.

/.github

# Ignore development files

/.devcontainer

# Ignore Docker-related files

/.dockerignore

/Dockerfile*

.dockerfile file in the project not only allows excluding unnecessary files and directories (e.g., GitHub workflows from the .github folder or JavaScript dependencies from the node_modules) from the context. It also helps to avoid accidentally adding sensitive information to the image. For example, the .env file that contains the environment variables or the master.key file that is used to decrypt the credentials.

Use Dive

All the optimizations mentioned above may seem obvious when explained. What to do if you already have a massive image, and you don’t know where to start?

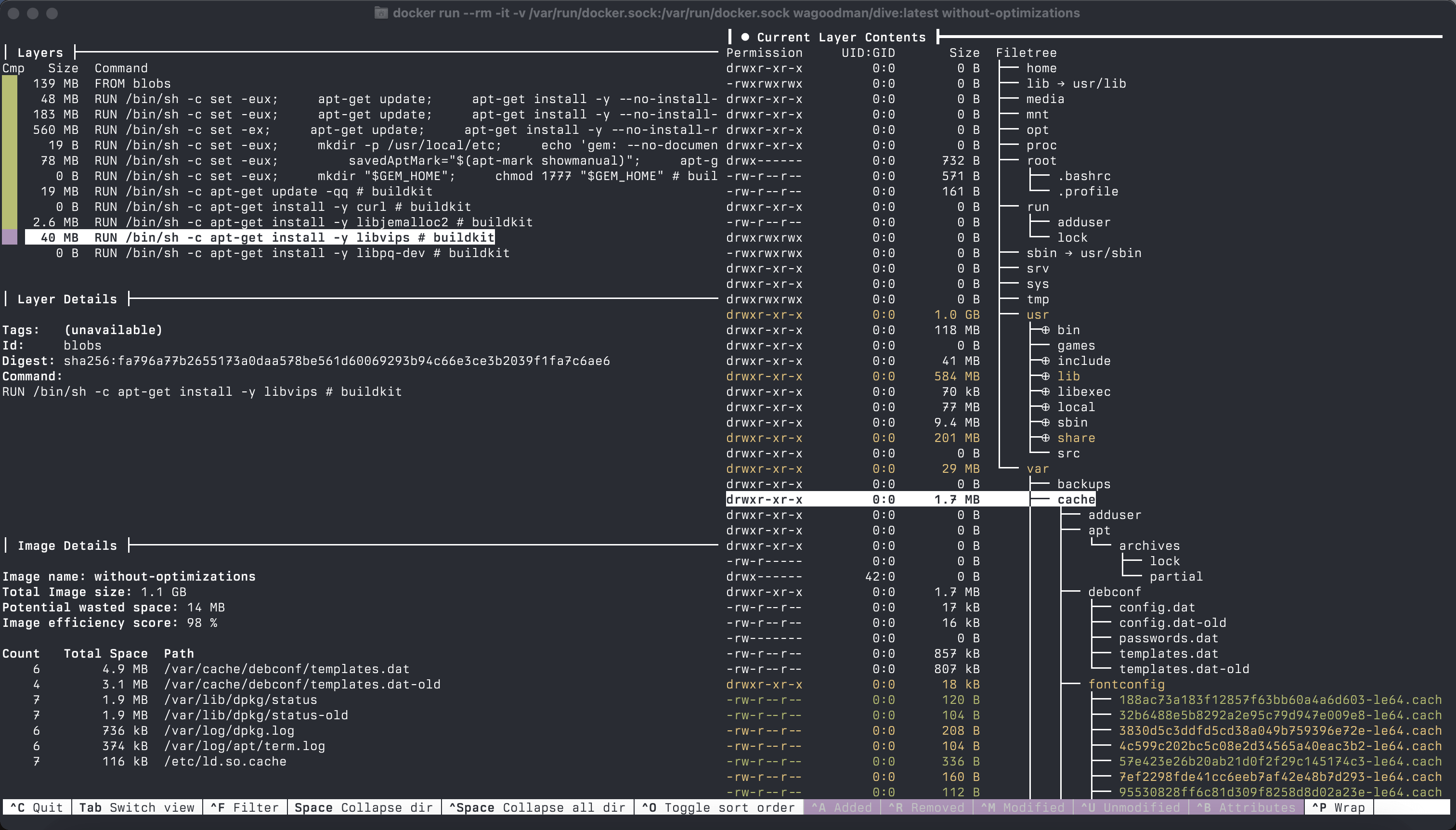

My favorite and most useful tool is Dive. Dive is a TUI tool for exploring a Docker image, layer contents, and discovering ways to shrink the image size. Dive can be installed with your system package manager, or you can use its official Docker image to run it. Let’s use the image from our worst scenario.

docker run --rm -it -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock wagoodman/dive:latest without-optimizations

In the screenshot above, you can see the inspection of our the most non-optimal image. Dive shows the size of each layer, the total size of the image, and the files that were changed (added, modified, or deleted) in each layer. For me, this is the most useful feature of Dive. By listing the files in the right panel, you can easily identify the files that are not needed and remove commands that add them to the image.

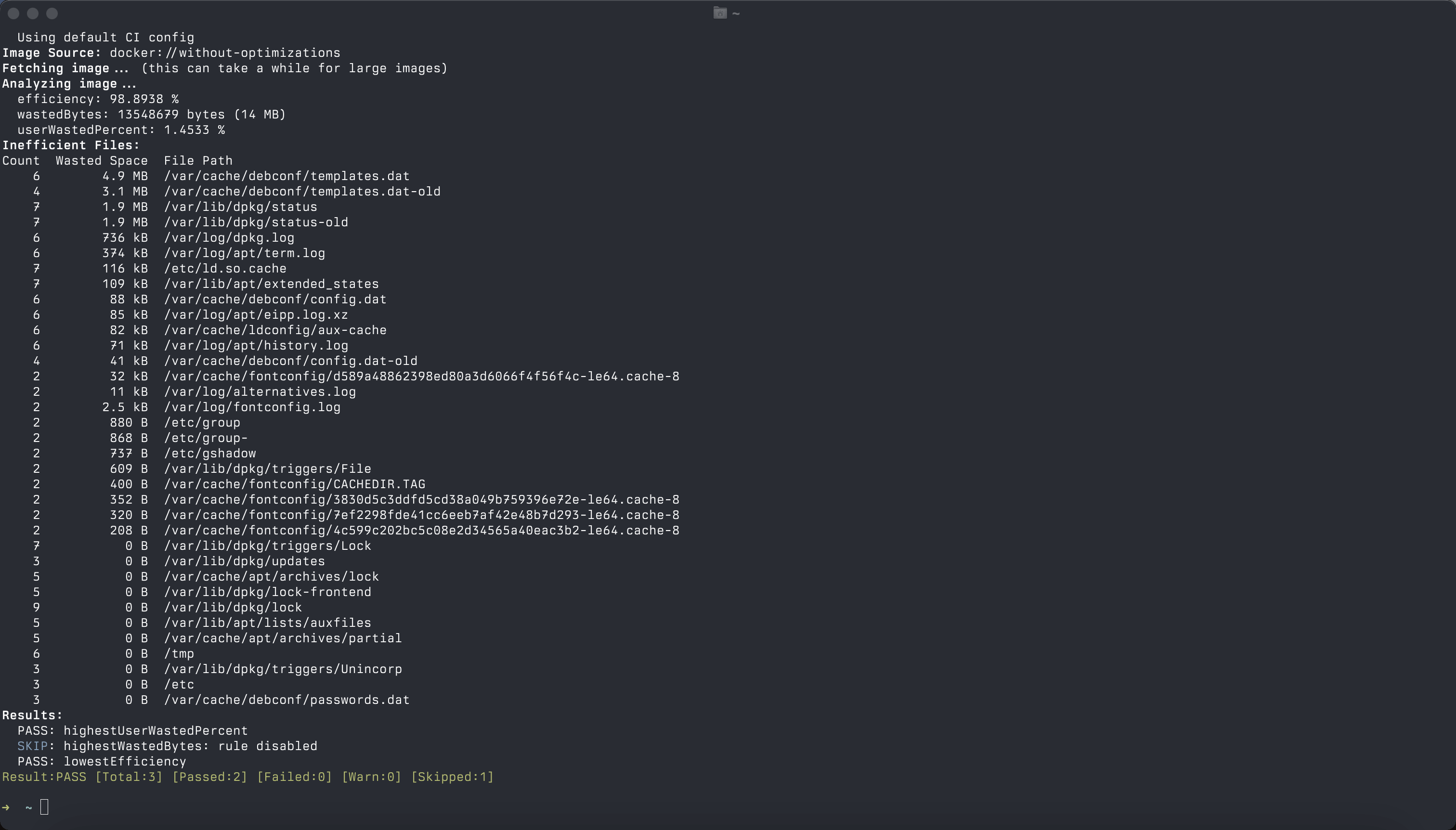

One thing that I truly love about Dive is that, besides having a terminal UI, it also can provide a CI-friendly output, which can be effective in a local development too. To use it, run Dive with the CI environment variable set to true, the output of the command is in the screenshot below.

docker run -e CI=true --rm -it -v /var/run/docker.sock:/var/run/docker.sock wagoodman/dive:latest without-optimizations

My personal preference is to use Dive on a scheduled basis, for example, once a week, to ensure your images are still in a good shape. In the upcoming articles, I will cover automated workflows I use to check my Dockerfile, including Dive and Hadolint.

Don’t squash layers

One approach to minimizing image size that I’ve seen is to try to squash the layers. The idea was to combine several layers into a single layer to reduce the image size. Docker had an experimental option --squash, besides this, there were third-party tools like docker-squash.

While this approach worked in the past, currently it is deprecated and not recommended to use. Squashing layers destroyed Docker’s fundamental feature of layer caching. Apart from that, while using --squash you could unintentionally include sensitive or temporary files from earlier layers in the final image. This is an all-or-nothing approach that lacks fine-grained control.

Instead of squashing layers, it is recommended to use multi-stage builds. Rails Dockerfile already uses multi-stage builds, I will explain how it works in the next article.

Conclusions

Optimizing Docker images, just like any other optimization, cannot be done once and forgotten. It is an ongoing process that requires regular checks and improvements. I tried to cover the basics, but they are critical to know and understand. In the next articles, I will cover more advanced techniques and tools that can help to make your Docker builds faster and more efficient.